The resurgence of urbanism – the desire to live and work in dense, compact central cities – in 21st century North America and Europe is often attributed to the inherent value of bringing diverse and talented people together in close proximity, which generates economic and cultural creativity.

But this dynamic has always been the value of cities, for millennia. So the resurgence of urbanism begs the question: if urbanism brings such benefits, why did urbanism decline so drastically in the 20th century?

In a review of Richard Florida’s new book The New Urban Crisis, I proposed that one factor was pollution, specifically the rise of industrial pollution in the 19th and 20th centuries. I’d like to delve into that idea in a bit more depth here. Of course, pollution is not the only factor. Other factors could include congestion, racism and xenophobia, crime, the changing price of fuel, and crowding and the desire for more living space. But I’d like to propose that pollution was one of the most important factors – both in the decline of urbanism, and (by its absence) in its more recent resurgence. I’m sure I’m not the first person to propose this, but I have not seen the idea widely cited in discussions of urbanism, so I think it bears repeating.

Cities have always been polluted. The concentration of people generates enormous amounts of waste (both sewage and household garbage) and the concentration of buildings makes it difficult to dispose of that waste. As well, cities generate craft and industrial activities that create their own forms of pollution. For example, throughout history tanneries for processing leather were notorious for the waste and stench they generated, and cities often banished them to specific locations where the effect of their pollution would be minimized. Disposing of waste has always been one of the primary concerns of city governments. Some built elaborate sewer systems; others simply hired people to collect waste or clean the streets. But these measures were not enough to keep the city healthy – demographic studies of European cities before the Industrial Revolution have shown that often more people died there than were born, and they only maintained and increased their population through in-migration from the countryside.

Before the industrial era, wealthy people who lived and worked in cities often also kept a residence in the countryside, which they would go to especially during the summer to escape the heat (heat that also intensified the effects of urban pollution). But they would return to the city for the business season because of all the advantages of urban living – as a place for business, politics and cultural activity (wealthy people who lived and worked in the country also often kept city residences for the same reason). So there was a balance, a push and pull between the vitality and the discomforts and dangers of urban life. The greater part of the population, of course, had less choice in the matter, but cities survived because, for migrants from the countryside, urban vitality remained a strong draw despite the disadvantages.

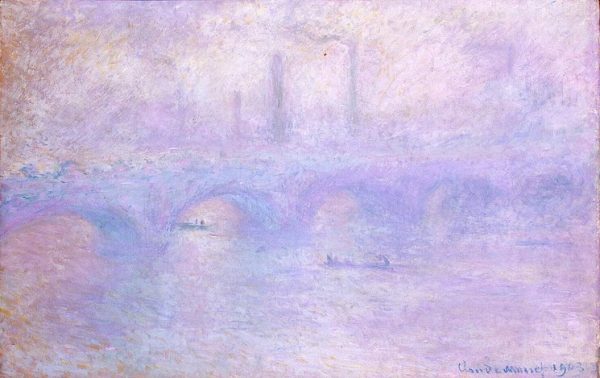

The advent of the industrial revolution in the 19th century tipped the pollution scales. It began with coal, which generated massive amounts of highly visible particulate waste. Coal fueled industrial plants, trains, and ships. It reached into the centre of cities because of the need for transportation links between industry, railways, and ports. It was also used for household heating, where its effects were even worse than the wood fires it replaced. The impact of coal on cities was massive, covering them in soot and smog. Buildings became blackened like never before, and we are still removing its impact from buildings in our cities. Smog, and the attendant health problems it creates, became endemic.

Claude Monet, Waterloo Bridge. Effect of Fog (1903). Monet’s paintings of London captured the effects of its intense smog

Other industrial processes exacerbated the effect. What had once been small-scale industries became massive. In Toronto, for example, the huge distillery of Gooderham + Worts, and the huge hog-slaughtering operations, both generated tons of other waste products and emissions.

This pollution had an impact on where the city’s inhabitants wanted to live. People recognized and understood that pollution had an impact on them, and they tried to avoid it if they could afford to do so. Have you noticed, for example, how in so many cities (Toronto included), the east side is poorer than the west side? It’s because the prevailing winds in Europe and North America are west to east, and they blow pollution to the east side. A fascinating study by economists Stephan Heblich, Alex Trew and Yanos Zylbergerg quantified this effect, identifying how 19th century pollution was dispersed eastwards and showing that the most polluted areas were also the poorest. In Toronto, the east side was always more working class compared to the more middle-class west side, and parts of the east side near dowontown are only starting to gentrify now that industry has mostly vanished from central Toronto.

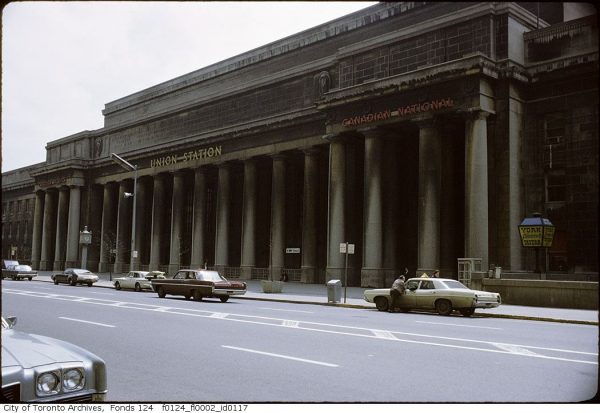

This effect was also true for the centre of cities, where coal-using ports and railway stations were situated, along with industries. Before the railway arrived, many of Toronto’s wealthy lived near the centre of the city, where they had easy access to their work spaces and the centres of power such as the courts, city hall and the legislature. But they gradually moved away as the port area became industrialized, further from the port (not to mention at a higher elevation and not downwind) to places like Rosedale and the Annex. Think of the grand mansions on Jarvis Street. Their owners didn’t leave them because they got better offers for the land – the mansions of Jarvis Street stayed in place rather than being replaced by bigger buildings, for the most part. They just up and left for cleaner locations as a pall of soot descended on their houses.

In the 20th century, coal use started to decline, and new sanitation measures meant the impact of sewage and household waste was greatly reduced. But new pollutants emerged – chemicals from chemical plants, and particulates, lead, and other pollution from the increasing number of gasoline-powered vehicles. These pollutants were less visible. But I would argue people could still tell that their atmosphere was unhealthy. People can tell that those around them are suffering more from illnesses, that their children are not as healthy as they should be, that the air doesn’t smell quite the way it’s supposed to. They can see and feel exhaust.

The result of these waves of pollution was that people moved out of the central city as soon as technology made it possible to do so and still commute into the city for work. The advantages of living in the city were not worth the degree of pollution they were exposed to. Cities became seen as intrinsically dirty and unhealthy, and it’s not a coincidence that ideas of “Garden Cities” and separation of uses appeared at the end of the coal-ridden 19th century. People were willing to travel longer distances to work specifically in order to avoid industrial pollution. The first round was the streetcar suburbs – people could live far away from their work and still commute in a reasonable amount of time (on non-polluting electric streetcars). After the Second World War, the advent of better highways, affordable cars and well-paying working class jobs meant that many more people were able to escape the pollution and move to greener pastures, now carefully separated from industrial uses by planners. Once expensive and desirable in many (though not all) areas, as evidenced by its large houses, the soot-blackened, particulate-full central city was largely abandoned as a place to live to people looking for affordable housing — the poor, immigrants, and bohemians.

But as the 20th century came to a close, pollution began to be greatly reduced. Coal was no longer used for fuel. De-industrialization meant that many of the factories near the centre of cities were abandoned. Stricter pollution controls meant that trains, ships, trucks and cars no longer generated anywhere near as much pollution as they had a few decades before. And new sources of downtown jobs – finance, technology, media – don’t generate pollution in the same way. The centres of cities are much, much cleaner now than they were in the 20th century, or for that matter than they ever were in history.

With the removal of this disincentive, the long-standing attractions of urban life are back at the forefront. The result is that people are flooding back into the centre of cities. Employers and their employees are taking over the spaces abandoned by industries, moving into cool renovated former-industrial loft spaces, or new office and condo buildings built on remediated industrial land. They can enjoy living and working amid the charming, defanged trappings of industry without enduring the reality of its polluted side effects.

The resurgence of active transportation and public space can also be related to this development. With less pollution spewing out of cars and sitting in the air, walking and cycling to work or leisure activities, and hanging out in public in parks or on patios, has become more of a joy and less of an endurance test for the lungs.

Not everyone is moving to the centre of cities, of course (although rising real estate prices suggest demand is greater than supply). Some people still prefer the larger spaces available in the suburbs. Certainly other factors are in play, too, such as a drop in crime (which could also be related to reduced lead pollution) and increasing congestion that extends commuting times. But the new vitality of central cities is a reflection of what happens when pollution is removed from the equation – while other factors have an impact, pollution seems to have been one of the core factors in the fall of urbanism in the 20th century, and its removal a key element in its resurgence.

If anyone knows of similar ideas or studies supporting this idea, please share them in the comments. This is just a hypothesis, of course, and one can think of various ways to study data to see if it holds up. For example, in Toronto one could study the change in incomes or property values after the introduction of coal emissions that affect particular areas (like my argument about Jarvis Street, above). I’m sure there are other ways to investigate this idea too, and I hope this piece will inspire others to dig into the question.

Images courtesy of City of Toronto Archives and arthermitage.org

The post Pollution and the fall and rise of urbanism appeared first on Spacing Toronto.